Hip-hop and the n-word, seen through King’s prism

This frigid Martin Luther King Day finds me at the office away from the office, a place most of you know as Starbucks, laptop open as I put some ideas on “paper.” Nothing you’ll see in the Star anytime soon, but that’s not a bad thing.

Follow me long enough and you’ll figure out that I think big, and when I have ideas I don’t just pitch stories. I pitch projects.

So when you see me at Starbucks it doesn’t mean I’m trying to spit out something to feed the voracious copy-consuming beast known as thestar.com. It means I’m refining an idea I can take to the woodshed, and that like the Pharcyde I’m trying to kick something that means something.

Martin Luther King Day can get you thinking like that.

Yes I realize that it’s an U.S. holiday and that I reside in Canada, where MLK Day isn’t legally recognized. But as an AmeriCanadian citizen I it’s not just my right but my duty to pause and recognize the life and work of the greatest American who ever lived.

I’m not sick so I called in patriotic.

Besides, if you think the United States’ borders contained King’s brilliance and influence, you’re not thinking big enough. And if you don’t realize that King wasn’t just a leader in domestic civil rights but a key player in the global struggle for human rights then you misunderstand the man’s legacy.

In between sentences on this particular blog post, in fact, I’m trading emails with Gary Freeman, a mentor, friend and intellectual sparring partner who lovingly cuffs me around the ring whenever the opportunity arises.

The conversation started with this New Yorker portrait of Tommie Smith and John Carlos and has since moved to Patrice Lumumba, whose death 50 years ago today wasn’t just condoned but facilitated by the U.S. government.

Along the way we touched on hip-hop, a tangent onto which our conversation veered when Gary came across Montreal Gazette story detailing how a fistfight between female spectators bought an early end to a Rick Ross concert.

Like me, Gary wasn’t suprised that concert ended that way.

Neither of us is C. Dolores Tucker, drawing a staight line between vulgar lyrics and violent behaviour, but you don’t need to be a hip-hop scholar to figure out that talentless rappers can always make millions pandering to the lowest common denominator.

Of course, that is the game we’re playing. Otherwise we would never have heard of Ross, or Wacka Flocka, or any tatted-up rap star who takes over the airwaves for a few months before flaming out and fading away.

And this peddling of hip-hop’s twin vices — vulgarity and violence — certainly isn’t new.

It’s been more than two decades since NWA dropped Straight Outta Compton, ushering in both the gangsta rap era and the idea authentic hip hop not only encompassed cursing but required it.

The gratuitous swearing and liberal sprinkling of the n-word on damn near every track turned off scores of critics, but listeners of all colours gravitated toward the gritty language and hip-hop experts defended it as the vernacular eloquence of the street.

Same with the the violence, derided by critics but upheld by defenders as an ugly yet authentic element of ghetto storytelling. Hip-hop, as Public Enemy frontman Chuck D. famously pointed out, was “Black America’s CNN.”

But now some of the people who stood between gangsta rap and its fiercest critics — even Chuck D, himself — realize that NWA’s true legacy wasn’t the liberation of hip-hop lyricists from censorship but the establishment of a branch of the music industry that turns huge profits as listeners both black and white drop big dollars on music that glorifies the pathologies that (stereo)typify ghetto life.

And as my good friend Bomani Jones points out on his blog, those of us who defended NWA back then also enabled the creators of the worst of hip-hop culture to produce the crap people like me spend all day trying to avoid.

In our email exchange Gary took that argument a step further, saying that any artist who in 2011 still drops N-bombs deserves to be vilified. Gary feels strongly about the n-word, and in this 2007 article he artfully blends memory and analysis to make a compelling case against it.

Transfer that analysis to hip-hop and it’s tough to disagree with him.

But I do.

Respectfully.

This isn’t to say that I support crappy hip-hop or advocate indiscriminant use of the N-word.

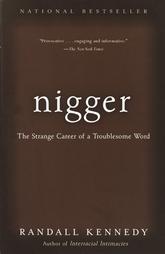

Instead I’m suggesting we move beyond the binary logic that forces us to view words like “nigger” and art forms like hip-hop as either positive or negative, with no room in the analysis for context.

People who think we can abolish the n-word like we did slavery need to remember two things about words.

First, they’re organic. They fade in and out of existence according to countless factors, but not according to anything we can legislate. When people are ready to stop using a word they will, and that word will disappear. If language didn’t work that way we’d still use the word “ruth” when we meant “mercy” and and “wherefore” when we meant “why.”

Second, for many words meaning depends heavily on context — the speaker, the receiver, the situation.

If I walk into my mom’s house and she says, “Hey, boy! I’ve been waiting for you!” I give her a big hug and tell her I’m glad to be home.

If I walk into the office and my boss says the same thing to me I’m calling my lawyer.

Same word, same definition, very different meaning when you change the context.

When you’re dealing with the N-word the stakes are much higher but the rules remain the same.

And while I accept use of the n-word in certain settings I reject the argument that the hip-hop generation was the first one to use the it as a term of endearment. Show me an African-American my age or older and I’ll show you someone who has probably heard parents, grandparents, uncles or aunts use the word in ways alternately playful, disdainful, loving and sarcastic.

Nor do I co-sign on the theory that “Nigga” is a term of endearment while “Nigger” is a pejorative.

If you believe that, then picture yourself in Cambridge Mass., surrounded by a mob of racist whites armed with chains, bats and language.

“Hey dahkie,” the gang’s leader shouts to you. “Get the hell outta Hah-vid yahd, ya re-tahd nigga!”

Does his use of the word “nigga” tell you he’s greeting a friend, or does the context plus the hurling of the n-bomb tell you he means trouble.

Exactly.

Whether you abhor or support of the n-word, or take it on a case-by-case basis, to regard its meaning and significance as static is to ignore the dynamic and adaptable nature of language.

Similarly, to dismiss any hip-hop artist who uses the n-word is to gloss over the fine points both of our language and of the art form.

I don’t say this to segue in to a litany of hip-hop artists I feel make music with a “positive message,” because it’s not fair to force hip-hop artists to make that choice, and because the litmus test for art isn’t whether or not it preaches a message I personally find comforting.

Sometimes we understand that.

To read The Great Gatsby is to reach a number of dreary conclusions about your fellow humans: Wealth corrupts; the rich are above justice; youth and beauty are about as sturdy as sandcastles.

Depressing stuff, yet did anyone ever accuse F. Scott Fitzgerald of sending a “negative message” with that novel, or was he simply free to create literature?

How much smaller would Shakespeare’s body of work have been if every time he sat down to write he worried about creating not just art but a play with a “positive message”? How would MacBeth have turned out under those constraints?

Or The Godfather?

The point here is that to tell a story well a stroyteller can’t worry about happy or sad endings, positive or negative images. The storyteller’s main concern is that the story makes you think, engage, empathize and think some more, and those rules don’t change when we’re dealing with hip-hop.

And they don’t change when an emcee chooses to use the occasional n-word to emphasize a point.

And what does any of that have to do with Martin Luther King?

Plenty.

I’m not going to pretend to know what Dr. King would think of hip-hop as an art form or as an industry, nor how he would weigh in on the n-word debate.

We can safely assume that he hated stereotype, and would have criticized strongly any music that used it to titillate then wring cash from white consumers all too ready to believe the worst about black folks (black consumers too, unfortunately).

But beyond that we don’t know for sure how he would react to the wide range of music now labeled “hip-hop.”

What i do know is that I woke up on the day set aside to commemorate Dr. King and his legacy and turned on a hip-hop song that inspires me the way scripture uplifts the religious. It contains exactly two n-bombs but I never felt conflicted playing it on a day that celebrates Dr. King.

What we know for sure is that he dreamt that we could all be judged not on appearances but on the content of our character.

Applying those principles to hip-hop means peering beyond foul language (including the n-word) to take in the quality of the story being told. If we can accept that the bloodshed in MacBeth is part of a masterpiece of a play, then we can accept that the word “nigga” in the first song I listened to this morning doesn’t diminish the literature in the lyrics.

And if you can’t accept that maybe you’re not listening to the right kind of hip-hop

To say it simple, points all well taken and well spoken.

Regarding your disagreement, you over-intellectualize the issue. Next you are going to write a overly-intellectualized justification for flying the Confederate flag. Only those who have a living memory of that era, who actually suffered racial discrimination and brutality, who smelled the cordite and tasted the fear of their own mortality as a pasty acrid slime on the back of their tongue when confronted by racist violence and brutality may understand. I challenge you to find one African American who actually went through the struggle who thinks that the use of the N-word is ever justified.

The history of the use of the word is bound up with slavery. That is beyond dispute. The first users of the word were slave masters. It was a derogatory term meant to dehumanize. Blacks picked up the use of the word from their oppressor. Its use continues that psychological and spiritual oppression. Just because you grew up hearing it as a “term of endearment” does not diminish its origins and primary purpose in the English lexicon. I heard it too: “My nigger” this and “my nigger” that”. Something happened to the user of the word once they were confronted with its etymology. Something happened to their self image and the way they looked at other blacks when they committed to stop using it. You were not there to witness gang-bangers declare truces and to declare they were no longer “niggers”. Your reference to MacBeth is so lame I’m shocked you tried to pull that off. So you went to school and read English lit. What did Shakespeare have to say about racial oppression and the enslavement of blacks or the genocide of the natives? You’re using white melodrama to justify white racist language? That’s really “organic”.

1. My parents came up in the same era you did and suffered many of the same racial slights, and still use the n-word occasionally, sarcastically, caustically, etc. depending on the situation. Remember when Malcolm X was lamenting his split from the Nation of Islam, and how a greed and personal ambition had corrupted an organization with noble goals? What did he say to a friend about it? He said “n*****s messed it up.” Or i could quote stokely (all the scared n*****s are dead) carmichael. I don’t say this to prove that prominent black thinkers and leaders sometimes dropped n-bombs but to reinforce that it’s every thinking person’s right to react to the word in the way he sees fit. Black folks my parents age and older know where that word came from and what it was meant to do, but that doesn’t mean that every time any black person uses it they do it out of a sense of self-hatred. I don’t need to tell you that African American speech has always dripped with subtlety and irony, and that we can apply those characteristics to the n-word too. Again, this isn’t to justify wanton use of a radioactive word, and i do think it’s completely overused in hip-hop and beyond, but we do need to recognize that meanings vary depending on situation and evolve over time.

2. Not using white melodrama to justify racist language. I’m saying that violence and violent language don’t necessarily diminish a work of art. Sometimes they’re an integral part of it. If you can’t see a parallel between the violence in MacBeth and the pointed vulgarity in certain hip hop songs then you’re not recognizing that certain hip hop artists have mastered their medium the way Shakespeare mastered his. Not comparing shakespeare to Rick Ross and Wacka Flocka. Not at all. I’m saying hip hop has its own Shakespeares, and guys whose music is worth exploring even if the occasional swear word or n-bomb might turn you off.

Morgan, your reference to Malcolm’s use of the word supports my position, not yours. Malcolm used the word to specify ignorant, self-hating blacks who were essentially self-destructive. He was a very smart and wise man who was a master word-smith. Even in his angriest moment, he chose his words with precision. If you are not confused about that, and are trying to imply that Malcolm X condoned the use of the word “nigger”, I don’t know quite what to say except “ouch” for you and hope that you were born with three feet ’cause you done shot holes in two of ’em.

Another great word-smith made an art-form out of using the word “nigger” in such a manner that can never be equalled by anyone – ever! Yet, he reached a point where he publicly swore off using the word “nigger”. Let’s let our own King Richard the Pryor have the definitive word on the subject: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEVmAbxC14g

I think we’re making the same point about the the word and the way Malcolm used it, Pops. Instead of swearing off the word completely he was faced with a situation where he felt only one word applied to what he saw unfolding and he deployed it masterfully. Again, i never said I supported the wanton dropping of n-bombs. We’re very much on the same page about Malcolm’s use of the n-word here — with precision, meaning and impact.

While I agree that if we simply dismiss everything a rapper (or any person says for that matter) says based on their willingness to use the term ‘nigger’ we may miss some pertinent, positive and/or relevant content… I worry about the message in this piece. To say when people are ready to stop using words they will and compare it to slang such as “wherefore” is comparing apples to oranges, or perhaps apples to burning crosses? the origins of this word, to Gary’s point, are bound in slavery, hatred and racism. But more than that – – to your point, it is still being used today in a derogatory manner.

If I started calling people “coons” would that be alright? – if my meaning behind it was endearing, if my intent behind it was loving? If the context was so-called appropriate? What about spook? Just because I may be able to justify it (which I can’t) doesn’t mean that the result would not be further dissension between our people.

I am not suggesting the ‘abolishment’ of the term in the same way I can’t support a ‘war against terror’ ….its logistically impossible. And after working with youth who use that word every day I know that the use is not always coming from a place of self hatred – just like if you straighten your hair it doesn’t mean you’re subjecting yourself to white beauty standards ….but I fear that we’re not asking the question why. Why do you want to have straight hair? so dudes will like you? so you can toss your hair over your shoulder? or just for a change in your look?

and why do you want to use the term “nigga” or “niggah” or “nigger” or however you want to spell it…because truthfully i can’t see a reason to want to not just use this word but use it in public spheres when it offends, insults and diminishes the struggle of our ‘own’.

What’s your take on the new edition of Huckleberry Finn that’s removing the 200-plus N-words from the novel and replacing them with ‘slave’?

http://www.vancouversun.com/Huckleberry+Finn+edition+replaces+word+with+slave/4059209/story.html

Very interesting debate on that word and its uses. I’m under the belief that simply removing a word does nothing, other than to have it replaced by another noun. The context in which a word is used is definitely in play. If we white wash the words from a culture how do we even have these kind of honest debates about racism which do not happen nearly enough. You can not bury a word and then pretend that we are somehow closer to racial equality as a result. Its more important to get rid of the ignorance which creates that kind of behaviour.

In case you missed it: “NAACP symbolically buries the word “nigger,” entertainers resurrect it ”

(http://www.blackpress.org/naacp.htm) That was a few years ago.

“Entertainers” are in the main only concerned with dolla billz y’all; & we know niggaz alwayz kill niggaz ova dolla billz. Its the sweetest form of suicide one’s oppressor could ever hope for.

Interesting there are no comments about the Richard Pryor video (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEVmAbxC14g); a more profound & complex statement of the liberating effect of waking up one morning and realizing that there is no such thing as a “nigger” cannot be found anywhere! From the undisputed greatest comic genius of all time; the “entertainer” who filled the well with the word that every “nigger/nigga/niggaz” spouting “entertainer” must drink from. Hmmm…no comments. Interesting.

The word Kaffir in South Africa has a similar trajectory and yet because it was widely considered a derogatory term “use of the word has been actionable in South African courts since at least 1976 – in Apartheid era South Africa, no less – under the offense of crimen injuria: “the unlawful, intentional and serious violation of the dignity of another. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaffir_racial_term)

And will our seasoned sports writer please tell us why the use of the word “nigger” is banned at World Cup soccer matches. Please step up and be consistent and say “nigger” should be used during World Cup play, (or hockey matches, or in any sports venue) if you dare defend it at all.

Remember the “doll test”? The original was done in 1939/40 by Drs. Kenneth & Mamie Clark. A recent one was done in 2005 by then 17-year-old film student Kiri Davis of Manhattan’s Urban Academy . Little black girls were shown light & dark dolls & asked to choose their preference. They more often preferred the lighter doll.

That’s what this debate is really about.

Exceptional people do exceptional things.

Great work Morgan.